Sleep Medicine is a broadly integrative field covering much of the human body and mind including the pulmonary, endocrine, respiratory, muscular and nervous systems. This means that many specialties make up sleep medicine, including...

- Internal medicine, which can incorporate, among other specialties:

- Pulmonary Disease

- Cardiovascular Disease (heart and vascular system)

- Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism (diabetes and other glandular and metabolic disorders)

- Adolescent Medicine (care of adolescents and young adults)

- Critical Care Medicine (care of patients in intensive care settings)

- Geriatric Medicine (care of older patients)

- Rheumatology (focus on joints and connective tissues)

- Sleep Medicine (sleep disturbances and disorders)

- Pediatrics

- Psychiatry/Psychology

- Neurology

- Family medicine, otolaryngology, and anesthesiology also overlaps with sleep medicine.

"The future ain’t what it used to be." —Yogi Berra

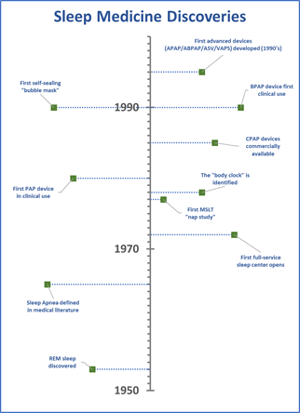

But Sleep Medicine it is a relative rookie when compared to these interconnected subspecialties in Medicine. Consider that before the 1970’s, there were no full-service sleep disorders centers in existence. And the CPAP (constant positive airway pressure) machine, the gold standard treatment for sleep apnea, did not become available until years later, in 1988. Prior to the 1980’s, tracheostomy was the only effective treatment for sleep apnea. In today’s Circadiance Blog, we’ll take a look back at how our field came to be, because by understanding our past we set the stage for things to come, and an upcoming blog when we can look forward to the future of Sleep Medicine.

There are over 80 sleep disorders, but the five most common types are:

Insomnia – the inability to fall asleep and stay asleep. This is the most common complaint in the primary care setting, after pain.(1) The symptoms of Insomnia are estimated to affect 70 million Americans including actor George Clooney and singers Madonna and Lady Gaga.

Insomnia – the inability to fall asleep and stay asleep. This is the most common complaint in the primary care setting, after pain.(1) The symptoms of Insomnia are estimated to affect 70 million Americans including actor George Clooney and singers Madonna and Lady Gaga.- Sleep Apnea – a sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by a significant number of breathing pauses, which afflicts 51 million in the U.S.,(2) including basketball legend Shaquille O’Neil (Shaq) and NFL hall of famer Reggie White, who died at age 43 from a heart arrhythmia (attack) exacerbated by untreated sleep apnea.

- Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) – unpleasant feelings in the legs such as a creepy, crawly or tingling feeling, along with a powerful urge to move them, reported by nearly 10% of the adult population responding to the 2005 NSF (National Sleep Foundation) Sleep in America poll, which corresponds to 21 million adults including talk show host Jon Stewart.(3)

- Daytime Somnolence (sleepiness) - being unable to stay awake during the day. This includes narcolepsy, which causes extreme daytime sleepiness and affects 200,000 in the U.S. including talk show host Jimmy Kimmel. Kurt Cobain, Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison, and Harriet Tubman are believed to have suffered from narcolepsy.

- Circadian Rhythm Disorder - problems with the sleep-wake cycle. They make you unable to sleep and wake at the right times. An estimated 10% of adult and 16% of adolescent sleep disorders patients may have a CRSD.(4)

- Parasomnia – refers to unusual behaviors that take place while falling asleep, sleeping, or transitioning to and from sleep, and include walking, talking, or eating. They are disorders of arousal that affect roughly 17% of children ages three to 13. At 15 and older, thought, the rate falls to between 2.9% and 4.2%.

The Stanford Sleep Clinic as the Model for Scientific Sleep Discoveries

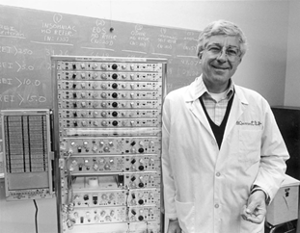

The existence of REM sleep (the dream stage) was not known until Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky’s discovery in 1953 at the University of Chicago, and it served as a turning point to establish ways of detecting different states of sleep. The work paved the way to our understanding and treatment of Narcolepsy, and much of this work took place at Stanford University. Narcolepsy is characterized by daytime sleepiness and waking intrusions directly into REM sleep. Research at Stanford in the 1970’s uncovered the value of stimulants for the treatment of narcolepsy,(5) and in 1977, the first description of a the multiple sleep latency (MSLT) daytime nap test for narcolepsy.(6) William Dement, who died earlier this year at the age of 91 and is credited as “the father of sleep medicine,” not only formed the Stanford lab and served as its first medical director, but his research and influence on colleagues brought about a number of scientific insights that precipitated an era of scientific research so fundamental to achieving our understanding of Sleep that it can’t be overstated.

The existence of REM sleep (the dream stage) was not known until Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky’s discovery in 1953 at the University of Chicago, and it served as a turning point to establish ways of detecting different states of sleep. The work paved the way to our understanding and treatment of Narcolepsy, and much of this work took place at Stanford University. Narcolepsy is characterized by daytime sleepiness and waking intrusions directly into REM sleep. Research at Stanford in the 1970’s uncovered the value of stimulants for the treatment of narcolepsy,(5) and in 1977, the first description of a the multiple sleep latency (MSLT) daytime nap test for narcolepsy.(6) William Dement, who died earlier this year at the age of 91 and is credited as “the father of sleep medicine,” not only formed the Stanford lab and served as its first medical director, but his research and influence on colleagues brought about a number of scientific insights that precipitated an era of scientific research so fundamental to achieving our understanding of Sleep that it can’t be overstated.

The Sleep specialty is so young that many of our original pioneers are still with us today, and still contributing. That was the case with Dr. Dement, whose passing on June 17, 2020 was a wakeup call that Sleep has come a long way, and many of today’s leaders have since taken time to reflect on his influence. The New York Times, in an article honoring his contributions, recalled him teaching the most popular class at Stanford, called Sleep and Dreams, that drew up to 1,200 students at a time. (If he caught students dozing, he’d famously wake them with a water gun.)(7) Early in his career, Dr. Dement had a number of accomplishments that are legendary among his peers. For example, during his medical internship at Mount Sinai Hospital, he opened a sleep lab in his apartment. He put up flyers to recruit study subjects and due to the proximity to Radio City Music Hall, many of the Rockettes enrolled—needless to say, the nightly traffic of dancing study participants into and out of his apartment almost got him evicted!

The Sleep specialty is so young that many of our original pioneers are still with us today, and still contributing. That was the case with Dr. Dement, whose passing on June 17, 2020 was a wakeup call that Sleep has come a long way, and many of today’s leaders have since taken time to reflect on his influence. The New York Times, in an article honoring his contributions, recalled him teaching the most popular class at Stanford, called Sleep and Dreams, that drew up to 1,200 students at a time. (If he caught students dozing, he’d famously wake them with a water gun.)(7) Early in his career, Dr. Dement had a number of accomplishments that are legendary among his peers. For example, during his medical internship at Mount Sinai Hospital, he opened a sleep lab in his apartment. He put up flyers to recruit study subjects and due to the proximity to Radio City Music Hall, many of the Rockettes enrolled—needless to say, the nightly traffic of dancing study participants into and out of his apartment almost got him evicted!

Dr. Dement’s guest appearance on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson and testimony before Congress in the 1980’s, which led to the creation of the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research, part of the National Institutes of Health, were watershed moments for the awareness of the importance of Sleep. At the time, most people thought sleep apnea was an atypical disorder affecting less than 2% of the population, and he presented research showing as much as 20% of the population was affected. The grants that resulted funded sleep studies for the next 20 years that led to an explosion of sleep centers and academic interdisciplinary sleep departments that together influenced how sleep medicine is practiced today.(8)

The clinical applications followed the scientific work on sleep disorders like Sleep Apnea, which has seen a dramatic diagnosis and treatment evolution in recent years. Until recently, sleep apnea was diagnosed only in the lab, using a full, polysomnography setup attended by a sleep technologist. Now, diagnostic care is split between in-lab evaluation which is focused on patients with comorbid medical conditions, and in-home evaluation using a Home Sleep Apnea Testing (HSAT) device which uses limited channels to measure for sleep apnea. The “big three” treatments for sleep apnea are CPAP, oral appliance therapy (OAT), and surgical procedures. The gold standard and most widely used approach, CPAP, hasn’t fundamentally changed since the 1980’s—it’s still a box with a blower in it that pushes room air into your lungs to open up your airway via a hose and mask interface—but the box has become smaller, the algorithms in the machine have become more sophisticated and able to adapt pressure levels to the patient needs, tubing can now be heated and receive humidified air, and the mask and headgear have seen tremendous developments.

Though most traditional CPAP masks continue to use plastic frames and silicone rubber on the skin, Circadiance was the first and only mask company to address comfort and compliance by developing a line of SleepWeaver cloth-based masks in 2007. The construction uses a material similar to ski-clothing, which has properties of flexibility, lightness, moisture permeability, and softness built-in. In recent comparison testing ahead of publication, SleepWeaver masks were found to exert 67% less pressure on the bridge of the nose than comparable masks made of traditional materials like plastic and silicone.(9) This has been a benefit to patients who would otherwise discontinue CPAP use because of an inability to tolerate the mask due to skin irritation and other forms of discomfort.

Insomnia, the most common sleep disorder and second most common complaint in the primary care setting (after pain), has historically been treated with medications until the development of behavioral interventions culminating in CBT-I (cognitive behavioral therapy for Insomnia), which today serves as an equally effective non-pharmacologic, first line treatment. Barbiturates were developed in the early 20th century and remained the primary prescribed hypnotic medications until the 1960s.(10) This was followed by the use of benzodiazepines in the 1970’s, then non-benzodiazepines in use today (beginning in the 1990’s).

Treatment of Parasomnias that occur outside of the REM period, called non-REM parasomnias, has taken a “low-tech” approach. These NREM “disorders of arousal,” indicating they take place during a transition from wake to sleep or back to wake, usually manifest in harmless behaviors like confusional arousals, sleepwalking, or bedwetting, with no memory of the event the next day. NREM Parasomnias are more prevalent in children and subside over time or when sleep hygiene improves by getting on a consistent bedtime / waketime schedule and avoiding sleep deprivation and stress. If sleepwalking has led to an injury, measures may need to be taken to improve safety in the environment including include removing sharp objects from the room, and keeping windows and doors locked.(11)

Some Parasomnias that occur during a REM period, like Rem Behavior Disorder (RBD), in which patients act out the content of their dreams, can be violent and dangerous for themselves and their bed partner. In such cases, pharmaceutical interventions are used.

Many of the sleep disorders centers have broadened to include the study of Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders (CRSDs). Circadian sleep-wake disorders were recognized only when chronobiology (the study of the body’s “internal clock”) and sleep research began to interact extensively in the last two decades of the 20th century. Like other sleep disorders, the knowledge about CRSDs developed as monitoring techniques improved. In the late 1980’s, portable activity monitors were able to provide for the first time insights on a mass scale into the rest versus activity cycles of humans. In 1978, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) was first identified as the location of the brain that controlled the body’s “clock” which regulates arousal levels. This led to the “two-process model we use today to predict alertness. There are many factors (usually visual, like from the blue light in screens) called Zeitgebers which influence the SCNs ability to regulate sleep, and the treatments for CRSDs involve controlling for these influences. For example, a delay in your sleep phase due to late night screen use can be controlled by eliminating all smartphones and TVs beginning one hour before bedtime.

Low Iron and genetic influences have been identified as markers for Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) though its cause is unknown. Patients with RLS who have low iron in the blood are supplemented with ferritin, and anti-seizure medications are becoming first line treatments, but typically the symptoms subside when sleep hygiene is improved but reducing alcohol and caffeine intake and improving bedtime routines.

The Sleep Technologist: from “Trade” to “Profession”

For most of the history of sleep technology, the job was basically looked at as a trade, not a profession. The barrier to enter the field and conduct studies was a high school degree and ‘on the job’ training. But with the signing of the Affordable Care Act into law ten years ago, everything changed. The ACA put in place conditions that would transition healthcare from fee-for-service to outcomes-based medicine, all while reducing costs. This means that expensive in-lab testing began to be replaced by home-based diagnosis and therapy for treatments like sleep apnea in patients with non-medically complex conditions, while patients with more complicated medical concerns and the expanded list of sleep disorders described in this blog continued to be studied in the lab. This scenario has forced sleep technologists to embrace a more rigorous set of skills and treatment modalities in an effort to become more competent at providing safe and effective care for patients.

For most of the history of sleep technology, the job was basically looked at as a trade, not a profession. The barrier to enter the field and conduct studies was a high school degree and ‘on the job’ training. But with the signing of the Affordable Care Act into law ten years ago, everything changed. The ACA put in place conditions that would transition healthcare from fee-for-service to outcomes-based medicine, all while reducing costs. This means that expensive in-lab testing began to be replaced by home-based diagnosis and therapy for treatments like sleep apnea in patients with non-medically complex conditions, while patients with more complicated medical concerns and the expanded list of sleep disorders described in this blog continued to be studied in the lab. This scenario has forced sleep technologists to embrace a more rigorous set of skills and treatment modalities in an effort to become more competent at providing safe and effective care for patients.

The modern sleep disorders center is staffed by sleep professionals who carry out a wide range of sleep services at a competency level that has never been seen before. One way to look at the evolution of the sleep disorders center is to compare it to the field of Cardiology. Just like the care of cardiovascular conditions has transitioned away from acute, invasive surgeries like bypass surgery (i.e., coronary artery bypass graft surgery), and toward interventional cardiology programs, which use cardiac angioplasty to open the coronary artery using minimally invasive methods, sleep labs are moving beyond diagnostic and toward interventional programs. Sleep professionals conduct titrations, retitrations, and perform CPAP accommodation studies called PAP-NAPs to manage chronic conditions like sleep apnea by treating (not testing) patients in order to open up their airways and “normalize airflow” in the way that interventional cardiology “normalizes blood flow” to and from the heart.

With this brief review, you can see how sleep disorders centers have evolved in their perspective on healing: from “sleep test” to “sleep disorders management,” and serve as the crucible for the evolution of the field of sleep medicine in both discoveries and resulting therapies. As we’ll see in an upcoming blog, the future of Sleep would be nowhere without these guiding principles to build upon.

—Matthew Anastasi, BS RST RPSGT, Clinical Coordinator Consultant, Circadiance

REFERENCES

1. Sateia, MJ, et al., Clinical Practice Guideline for the Pharmacologic Treatment of Chronic Insomnia in Adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med, 2017. 13(2): p. 307- 349.

2. Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):687-698.

3. Phillips B, Hening W, Britz P, Mannino D. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome: results from the 2005 National Sleep Foundation Poll. Chest. 2006 Jan;129(1):76-80. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.76. PMID: 16424415.

4. Kim MJ, Lee JH, Duffy JF. Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2013;20(11):513-528.

5. Mignot EJ. History of narcolepsy at Stanford University [published correction appears in Immunol Res. 2015 Jun;62(2):253]. Immunol Res. 2014;58(2-3):315-339.

6. Carskadon MA, Dement WC, Mitler MM, Roth T, Westbrook PR, Keenan S. Guidelines for the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT): a standard measure of sleepiness. Sleep. 1986;9(4):519–524.

7. Sandomir R. Dr. William Dement, Leader in Sleep Disorder Research, Dies at 91. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/27/science/dr-william-dement-dead.html. Published June 27, 2020. Accessed November 18, 2020.

8. Hagerty JR. William Dement Diagnosed America as Sleep-Deprived. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/william-dement-diagnosed-america-as-sleep-deprived-11594389600. Published July 10, 2020. Accessed November 18, 2020.

9. Anastasi M, et al. Comparison of PAP Interface Pressure on the Nasal Bridge: Soft Cloth vs. Traditional Masks. Abstract submitted for publication. 2020.

10. Neubauer DN. The evolution and development of insomnia pharmacotherapies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S11-S15.

11. Markov D, Jaffe F, Doghramji K. Update on parasomnias: a review for psychiatric practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(7):69-76.