SleepWeaver got its start in 2006, when David Groll, the company’s founder, first pinpointed the problems inherent in existing PAP interface designs. Having developed, manufactured and sold medical devices for over 30 years, and equipped with a formal post-secondary education in Biomedical Engineering with a Master’s degree in Manufacturing Systems Engineering, he was well versed in the needs of mask users—and he could see that the decades-old plastic technology was not really serving those needs. He noticed two problems with traditional masks: the air pressure required to seal the mask on the face compromised the blood flow to the skin, and moisture build up on the skin, both of which lead to skin discomfort and promote mask non-adherence.

He knew there had to be a better way. His stroke of inspiration came when he realized that no one wears plastic pajamas to bed, so why are we making people wear plastic masks on their faces? This led to exploring different mask materials and, in 2007, the SleepWeaver mask was born to solve this problem.

In the current healthcare environment, the field of Sleep has taken a second look at fundamentally changing the approach to CPAP masks and how they are made. The following four factors put the SleepWeaver line of masks front and center because of their focus on skin-friendly material and flexibility to accommodate a variety of faces, lifestyles, and patient types:

1) In the 10 years since passing into law the Affordable Care Act of 2010, patients have increasingly been taking a more active role in their healthcare decisions and that includes expecting, even demanding, better fitting masks.

2) Also brought on by ACA, providers must find ways to help their patients achieve stringent insurance compliance targets, and they must tilt the compliance odds in increasingly complex patient populations.

3) The third driver to personalized care is the shift to telehealth where telemedicine consults and remote mask fittings have replaced in-person interactions both in the lab and in the clinic setting.

4) Finally, the post-COVID-19 emergency world is seeing an investment in infection control through reductions in multi-patient reuse in devices like PAP masks—’Get it right the first time,’ is code for preventing mask waste and cross-contamination.

The shift to remote care is affecting every area of Sleep care: a) Sleep technologists, clinical sleep health educators, and RTs as they perform mask selection and fittings; b) Qualified healthcare providers (QHCPs) (e.g., sleep physicians; nurse practitioners) as they put together a sleep apnea care treatment approach; c) DME specialists as they select and fit masks furnished with a “patient choice” order.

In each of these pathways, the patient is the common stakeholder with an active role in the selection and fitting process.

Compliance is key. In the case of PAP therapy, the gold standard treatment for OSA, compliance hovers around 50% for OSA patients, and 10-20% of patients reject therapy in the first night. Compliance is determined in large part by providing patients the correct treatment for their condition the first time. The name of the game is compliance.

How do patients achieve CPAP compliance? The reason for this is that a key determinant of PAP therapy success is found in the mask interface itself: It has been reported that half of CPAP patients experience mask-related adverse effects, such as leaks, pain, pressure ulcers on the bridge of the nose, nasal congestion, and a dry mouth or nose. Also, the type of interface has been found to exert an influence on therapy tolerance and adherence.

Overall, available data shows that a good first experience during the implementation of treatment (during the first week) is crucial for long-term adherence. Therefore, proper mask selection has been shown to be central to facilitating a positive experience.

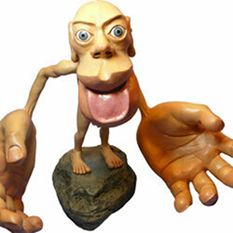

Homunculus and the PAP mask. The part of the PAP mask with the greatest responsibility for determining compliance (patient acceptance) and effectiveness (seal), however, is the cushion. The mask cushion is the interface between the skin, the frame, and the headgear. The cushion is critical because it makes up the majority of contact with the most sensitive areas of the face.

Homunculus and the PAP mask. The part of the PAP mask with the greatest responsibility for determining compliance (patient acceptance) and effectiveness (seal), however, is the cushion. The mask cushion is the interface between the skin, the frame, and the headgear. The cushion is critical because it makes up the majority of contact with the most sensitive areas of the face.

Homunculus is Latin for "little man.” The sensory and motor Homunculi were created to show how our bodies are represented within our brains, specifically in the cortical areas. The Homunculus medical representation shows which regions of the face are most richly innervated and thus sensitive to mask application. As you can see, the parts of the body that proportionally take up most real estate in the brain are the hands, tongue, lips nose and eyes. This matters for patient comfort because the bridge of the nose and area around and inside the mouth are most sensitive in the body, by design. So think about this: Let’s say a patient is diagnosed at the age of 50. That’s 10 years of a mask touching some of the most sensitive skin on the body.

Homunculus is Latin for "little man.” The sensory and motor Homunculi were created to show how our bodies are represented within our brains, specifically in the cortical areas. The Homunculus medical representation shows which regions of the face are most richly innervated and thus sensitive to mask application. As you can see, the parts of the body that proportionally take up most real estate in the brain are the hands, tongue, lips nose and eyes. This matters for patient comfort because the bridge of the nose and area around and inside the mouth are most sensitive in the body, by design. So think about this: Let’s say a patient is diagnosed at the age of 50. That’s 10 years of a mask touching some of the most sensitive skin on the body.

Pressure ulcers are a type of injury that breaks down the skin and underlying tissue. When an area of skin, usually over a bony prominence, is placed under constant pressure for certain period causing tissue Ischemia or inadequate blood supply, cessation of nutrition and oxygen supply to the tissues and eventually tissue necrosis.

Pressure ulcers are a type of injury that breaks down the skin and underlying tissue. When an area of skin, usually over a bony prominence, is placed under constant pressure for certain period causing tissue Ischemia or inadequate blood supply, cessation of nutrition and oxygen supply to the tissues and eventually tissue necrosis.

The field of wound care reveals important insights into the formula for pressure ulcer prevention, and it goes beyond pressure alone.

According to the Minnesota Pressure Ulcer Initiative, four factors cause skin irritation: mask material, pressure, shearing and moisture. Each of these is interrelated and has implications for this section on mask composition and both patient comfort and compliance. If a patient has skin issues, both comfort and compliance suffer.

With most CPAP patients on humidified air, moisture is a common factor in skin breakdown. Breathable materials work best to prevent the accumulation of moisture.

The weight of a mask and the pressure from strap tightening impacts pressure on skin and can cause a pressure ulcer. Therefore, lighter pressure is better and breathable materials are essential to prevent accumulation of moisture.

What matters for skin integrity is a) pressure and b) the material it comes in contact with.

The take home from all this is that you need to find the combination of mask type and material which is the lowest weight, least reactive and most permeable whenever there is a skin sensitivity issue from a patient.

Changes in healthcare delivery have shifted the economic burden to patients. As a result of having to pay higher deductibles, co-pays, etc., patients are becoming more involved in their healthcare decisions and being selective about their care. This means that patients expect masks to fit properly and comfortably, and manufacturers have responded by putting significant amounts of R&D into making better masks. No area has been impacted more than the type of material that CPAP masks are made of.

For over 35 years, the technology behind Positive Airway Pressure has been refined, but for most users it still makes use of a hard plastic and silicone mask interface. Most CPAP interface-producing companies have likewise not evolved their approach to mask construction, and patients are paying the price with discomfort and poor compliance. In all the years since the first commercial CPAP masks were developed in 1985, CPAP compliance still hovers at a meager 50%.

But Circadiance has transformed the mask model, with a line of masks that avoids the use of frames altogether and does not make masks with Silicone, plastic or foam. The SleepWeaver line, instead, is made up of a cloth material similar to ski clothing that consists of mostly polyester with some nylon and elastic weaved in.

Because of its lightweight, flexibility inherent in being composed of cloth, and moisture permeability, it produces the least irritating effect the skin.

Circadiance offers five SleepWeaver nasal masks, including Advance, Advance Small, Advance Pediatric, Elan, 3D, and a full face mask called Anew.

|

Advance (Nasal) Therapy Pressures 4-20 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 12.9-40 LPM Patient weight > 30 Kg (66 lbs) Mask Sizes: One Size 5 Colors: beige/ blue/ pink/ leopard/ camouflage |

3D (Nasal) Therapy Pressures 4-20 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 18-50 LPM Patient Weight > 30 Kg (66 lbs) Mask Cushion Sizes: One Size Headgear Sizes: Regular Neck Size 16 Inch and Under; Large 16.5 Inch and Above. |

Élan (Nasal) Therapy Pressures 4-20 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 14-45 LPM Patient Weight > 30 Kg (66 lbs) Mask Sizes: Small, Regular & Large Headgear Size: Universal/ One Size |

|

Anew (Full face) Therapy Pressures 4-30 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 16-67 LPM Patient Weight > 30 Kg (66 lbs) Mask Sizes: Small, Regular & Large Headgear: Small and Regular (but fits large) |

Advance Pediatric (Nasal) Therapy Pressures 4-20 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 18-50 LPM Patient Age: 2-7 Years Mask Sizes: One Size One Size Pediatric 5-Point Adjustable Headgear |

Advance Small (Nasal) Therapy Pressures 4-20 cm H2O Fixed Leak Rate: 17-45 LPM Patient Weight > 30 Kg (66 lbs) Mask Sizes: One Size Colors: Beige Universal Headgear Size |

In order to control skin irritation, many clinicians use a liner or gel pad between the skin and silicone masks. The approach that the SleepWeaver masks take is to make the mask itself out of a skin-friendly material.

The Principle Behind “Skin-Friendly” Soft Cloth SleepWeaver Masks

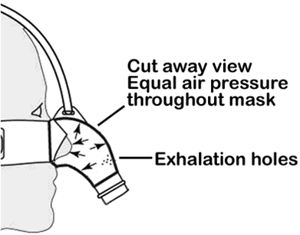

SleepWeaver achieves a good seal and quiet operation using the properties of a balloon. When a balloon is inflated, all points inside the balloon are at the same pressure. The SleepWeaver takes advantage of this property. The pressure inside of the mask is the same at all points. So the pressure being applied to the patient for their CPAP therapy is the same pressure that pushes the mask against the patient's skin. This creates a good seal between the cloth of the mask and the skin of the patient. There are several advantages of this method over conventional CPAP masks.

SleepWeaver achieves a good seal and quiet operation using the properties of a balloon. When a balloon is inflated, all points inside the balloon are at the same pressure. The SleepWeaver takes advantage of this property. The pressure inside of the mask is the same at all points. So the pressure being applied to the patient for their CPAP therapy is the same pressure that pushes the mask against the patient's skin. This creates a good seal between the cloth of the mask and the skin of the patient. There are several advantages of this method over conventional CPAP masks.

-The mask conforms to the patient’s face, providing a very good seal.

-Minimal tension in headgear straps.

-The pressure is the same at all points, so there are no localized pressure points that can create pressure sores.

In addition, because the mask material is moisture-permeable while not allowing air to pass through means it allows the skin to evaporate instead of trap moisture, all while retaining the all-important air seal to prevent leakage of CPAP pressure.

SleepWeaver mask cloth materials, aside from being skin-friendly, are inherently flexible. This means that each style of SleepWeaver can accommodate a wide variety of facial shapes. This contributes to ease of mask matching for patients who are increasingly being fitted remotely. OSA, after all, is a complex and heterogeneous chronic disease. Patients don’t have the luxury of being able to sample a half dozen masks in a sleep lab or DME service center if they are being fit remotely, and this is the unsung value of having a SleepWeaver be your first choice mask: it is more likely to “fit” your unique facial makeup, lifestyle needs, and provide a comfortable cushion against your skin to promote optimal compliance. Early mask comfort for CPAP compliance, after all, is the key to a successful long-term sleep apnea treatment. And SleepWeaver masks check off all the boxes to set you up for CPAP success.

—Matthew Anastasi, BS RST RPSGT, Clinical Coordinator Consultant, Circadiance

REFERENCES

Anastasi, M. W. (2019, May). Chapter 46: Positive Airway Pressure Therapy: Basic Principles. In Lee-Chiong, T. D., Mattice, C., Brooks, R (Eds.), Fundamentals of Sleep Technology 3rd (third) Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Egesi A, Davis MD. Irritant contact dermatitis due to the use of a continuous positive airway pressure nasal mask: 2 case reports and review of the literature. Cutis. 2012;90(3):125-128.

Epstein LJ; Kristo D; Strollo PJ; Friedman N; Malhotra A; Patil SP; Ramar K; Rogers R; Schwab RJ; Weaver EM; Weinstein MD. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5(3):263–276

M. Kohler, D. Smith, V. Tippett, and J. R. Stradling, “Predictors of long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure,” Thorax, vol. 65, no. 9, pp. 829–832, 2010.

Maruccia M, Ruggieri M, Onesti MG. Facial skin breakdown in patients with non-invasive ventilation devices: report of two cases and indications for treatment and prevention. Int Wound J. 2015;12(4):451-455. doi:10.1111/iwj.12135

Neuzeret, P.-C. & Morin, L. (2017). Impact of Different Nasal Masks on CPAP Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Randomized Comparative Trial. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26780403/

Ryan, S. et al. “Nasal pillows as an alternative interface in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome initiating continuous positive airway pressure therapy,” Journal of Sleep Research, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 367–373, 2011.

Positive Airway Pressure Titration Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical Guidelines for the Manual Titration of Positive Airway Pressure in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2008;4(2):157-171.

Quality & Patient Safety. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mnhospitals.org/quality-patient-safety/current-safety-quality-initiatives/pressure-ulcers

Roy, S. (2020, May 22). How Is the Coronavirus Impacting Sleep Medicine Professionals? Retrieved from https://www.sleepreviewmag.com/practice-management/money/financial-management/coronavirus-impact-sleep-medicine/

Shapiro, G. K. & Shapiro, C. M. “Factors that influence CPAP adherence: an overview,” Sleep and Breathing, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 323–335, 2010.

White, C.C. et al. (2012). Evaluations of interventions to treat and prevent pressure ulcers associated with mask interfaces during pediatric non-invasive ventilation. Respiratory Care, 57(10), 1787.