Here, there, and everywhere across our blue planet, nearly one million of us suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), with 54 million right here in the United States (1). Constant positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the gold standard and most widely prescribed treatment for OSA (2). For over 35 years the technology has been refined, but for most users it still consists of a box with a fan in it connected by tubing to a plastic and silicone mask interface...

Internationally some 5-50% of OSA patients recommended CPAP either reject this treatment option or discontinue use within the first week. 12 to 25% of the remaining patients may be expected to have discontinued its use at 3 years (3). Compliance is the greatest hindrance to successful treatment with CPAP (4).

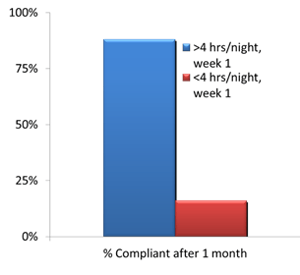

CPAP compliance early on predicts compliance down the road. In a study by Budhiraja (5), patient compliance with CPAP was measured at Day 7 and again at Day 30. Those that used CPAP >4 hours each night for that first week were much more likely to be compliant after 30 days than those who initially used CPAP for <4 hours. This goes to show that early interventions for CPAP compliance are critical to long-term success.

The most exhaustive meta-analysis of compliance research compared the efficacy of mechanical vs. psychological/educational interventions was compared in 1007 participants across 24 studies. The authors (6) found, “The evidence in support of Bi-PAP, self-titration and humidification is lacking. There is some evidence that psychological/educational interventions improve CPAP usage.”

In my clinical experience as a registered sleep technologist, there are numerous barriers that patients cite in their refusal of CPAP. This collection of real feedback from patients includes:

"It feels weird."

"I can’t breathe."

"No big deal because the doctor didn’t tell me about it, his assistant did."

"What happens if there is a blackout?"

"I feel like I’m suffocating or drowning."

"I heard horror stories from other people."

"I travel...too tough to work it into my routine."

"I am going to drown in it."

"It’s too loud; I’m not going to get to sleep."

"I don’t like anything on my face."

"I am afraid I am going to die."

Complaints about CPAP are multiple, varied and often conflict with one another. Patient reasons often cite external cause for refusing treatment without insight into why. 11-28% of patients experience Claustrophobia (7). These real world barriers in the lab point to causes that go beyond the purely physical and mechanical operation of the CPAP device, and signal the need for what’s called a Behavioral Sleep Medicine (BSM) approach which is designed to address psychological factors.

What is Behavioral Sleep Medicine? BSM is an expanding area of the sleep field that focuses on the evaluation and treatment of sleep disorders by addressing behavioral, psychological, and physiological factors that interfere with sleep (8).

BSM assumes that OSA improves when both the body and mind are tended to. This way of looking at OSA is as a mind-body disorder.

Making a long-term change in any behavior as critical to good health as CPAP usage is indeed complicated. The standard care approach to CPAP acceptance is education, with the assumption that if patients understand why CPAP important, they will use it. But this approach is not working, and the compliance data bears this out. That is because behavior change is more complicated than that!

Indeed, few effective strategies have been developed to improve CPAP adherence. Most are aimed at improvement of equipment and the CPAP device itself. The critical period for long term adherence requires a more holistic intervention during the first week, and here are a few of the best BSM techniques toward that end:

- Exposure Therapy (9)

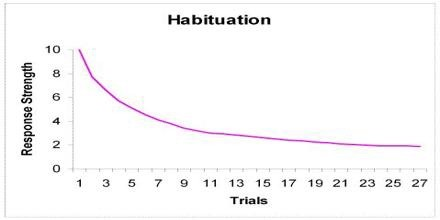

Many patients worry about the mask, so exposure therapy directly deals with mask problems and is extremely effective for specific fears and phobias. Exposure Therapy works by using the psychological principle called habituation, in which a novel (i.e., new) stimulus causes a physiological reaction, but repeated exposure to the same stimulus causes reduced reaction, and then no reaction. It is a learning process, also called “de-sensitization.” Habituation combats claustrophobia, which is known as a “prepared phobia” in that it doesn’t require prior learning to exist. Some of the symptoms of claustrophobia include:

Palpitations / increased heart rate

Dry-heaving, and/or gagging

Sweating

Trembling or shaking

Shortness of breath

Feeling of choking

Chest pain or discomfort

Nausea or abdominal distress

Feeling dizzy, lightheaded, or faint

De-realization / depersonalization

Fear of losing control or going insane

Sense of impending death

Numbness or tingling

Chills or hot flashes

Here are some practical approaches that you can use at home to reduce or even prevent the claustrophobic response to CPAP therapy (10):

- First, when you are first selecting a mask, choose the lightest and most comfortable material against the skin that is out of your field of vision. Circadiance® makes an all-cloth line of SleepWeaver® masks which by their design of being made of a material used in clothing are among the lightest and most comfortable available to patients. A SleepWeaver™ mask should be one of your first line choices if comfort, compliance and/or claustrophobia issues are important to you.

- Next, use the manufacturer-supplied sizing gauge to determine your mask size.

- Without attaching headgear, turn on machine to low setting and hold your mask to your nose and/or mouth, if possible (note: some masks are not designed to be held in place without headgear in place first). This will provide more of a feeling of control and setup a “hierarchy,” or gradual stepwise introduction of the stimulus (i.e., CPAP.)

- Practice breathing with CPAP for an extended period, and be ready for some resistance from the machine while you exhale—by reminding yourself to breathe in and out through the nose with your mouth closed this will facilitate accommodation to the habituation and exposure process and allow you to get to the next step.

- At the point when you develop a manageable comfort with the machine, you are ready to fully attach mask and continue (exposure hierarchy).

- Before going to sleep, practice removing the mask and headgear without assistance which will provide a further sense of control to stop and start treatment when you need to at night.

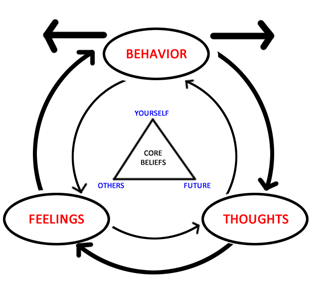

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (11)

This approach to increasing CPAP compliance allows for a multi-component conversation with a sleep physician or PhD therapist in the areas of:

a. Step 1: Education about sleep apnea, CPAP, benefits and barriers

b. Step 2: Models showing successful CPAP use

c. Step 3: Discussion and behavior modification

A practical scenario would involve reviewing a slide presentation with your sleep doctor, reviewing a CPAP machine and mask, viewing a 15-minute video and info booklet, then participating in a group session with a cognitive behavioral therapist. A CBT study used just this approach and the patients that followed this treatment yielded showed an almost 3 hr. (!) increase in CPAP usage (12). - Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) (13)

This is a process developed by Dr. Mark Aloia and colleagues and is based on Motivational Interviewing (MI) (14). Based on a treatment for alcoholism, the goal is to create a safe, neutral therapeutic space for patients to increase the importance of change. MI is specifically designed for behavior change for:

Alcohol/other addictions

Weight loss

Smoking cessation

Diabetes care

PAP compliance

Any health change

Here is an overview of the MET process:

- Assessment of motivation to use PAP

- Rate on a scale of 1-10 your readiness to change, motivation to make a change, and the reasons behind it.

- Education and information on how CPAP works and the health benefits from treating your OSA

- Review of diagnostic sleep study results

- Review of symptoms

- Talking about what led you to seek treatment?

- Review mortality graph

- Reflect on long-term consequences of untreated OSA.

- Review titration study

- Show effectiveness of CPAP in obliterating respiratory events including apneas and other “breathing pauses”.

- Values assessment

- Through a conversation with a therapist, or self-talk, there is often revealed a discrepancy or mismatch between current sleep apnea symptoms and what your life goals are.

- Decisional balance exercise

- Examine pros and cons of using and not using CPAP

- Highlight ambivalence and normalize this as part of the process (i.e., find a way to “sit with” your ambivalence until you are ready to take action)

One study (15) found that older adults receiving an MET treatment used CPAP on average 3.2 hrs. per night longer than control patients after 3 months. Another study (16) compared effectiveness of standard care (SC), education (ED) and MET and found significant improvement in adherence using MET with Ambivalent group (those that use PAP 2-6 hrs.). - Assessment of motivation to use PAP

Now that we have established the principles of BSM, and validated its effectiveness, where can you find these principles put into practice? The answer, increasingly, is everywhere.

Behavioral Sleep Medicine principles form the foundation of many smartphone apps and wearables (e.g., Fitbit, Jawbone, Misfit, etc.) which track food intake, sleep and exercise and other activity data. The data itself is just numbers. It requires a BSM context to provide the meaning that is necessary to promote behavior change (17).

But the less technological approach will always be a face-to-face consult with a sleep physician or behavioral sleep medicine specialist:

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine allows you to search for a certified sleep center here: http://sleepeducation.org/find-a-facility

The Society of Behavioral Sleep Medicine website offers a directory for finding a CBT-I behavioral sleep medicine provider here: https://www.behavioralsleep.org/index.php/united-states-sbsm-members

The take home message for CPAP adherence is this: CPAP adherence is a big problem, but there are tools to address it, both low-tech and high-tech alike.

REFERENCES

- Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):687-698. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5

- Patil SP, Ayappa IA, Caples SM, Kimoff RJ, Patel SR, Harrod CG. Treatment of Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea with Positive Airway Pressure: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(2):335-343. Published 2019 Feb 15. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7640

- The Role of Behavioral Interventions in CPAP Adherence (2010) Anstella Robinson, MD, FCCP, FAASM. Stanford University Sleep Disorders Center

- Weaver TE, Sawyer AM. Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea: implications for future interventions. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:245-258.

- Budhiraja, R., Parthasarathy, S., Drake, C.L., Roth, T., Sharief, I., Budhiraja, P., et al. (2007). Early CPAP use identifies subsequent adherence to CPAP therapy. Sleep, 30(3), 320-324.

- Haniffa M, Lasserson TJ, Smith I (2004). Interventions to improve compliance with continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea (Review). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 4 Art No: CD003531-pub2.

- Lewis, K.E., Seale, L., Bartle, I.E., Watkins, A.J., & Ebden, P. (2004). Early predictors of

CPAP use for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep, 27, 134-138. - Shapiro, G. K. & Shapiro, C. M. “Factors that influence CPAP adherence: an overview,” Sleep and Breathing, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 323–335, 2010.

- Jewish Nevada. The Danger of Habituation | Jewish Nevada. https://www.jewishnevada.org/blog/the-danger-of-habituation. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- American Association of Sleep Technologists. AAST Technical Guideline: Positive Airway Pressure Acclimation and Desensitization (2012). Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/matth/AppData/Local/Temp/Temp1_Guideline%20Review%20Project.zip/Review%20Project/PAP%20Acclimation.pdf

- File:Depicting basic tenets of CBT.jpg. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Depicting_basic_tenets_of_CBT.jpg

- Richards D, Bartlett DJ, Wong K et al. Increased adherence to CPAP with a group cognitive behavioral treatment intervention: a randomized trial. Sleep 2007;30(5):635-640.

- Inspire Malibu. Getting Motivated With Motivational Enhancement Therapy. Inspire Malibu. https://www.inspiremalibu.com/blog/non-12-step/getting-motivated-with-motivational-enhancement-therapy/. Published December 6, 2019. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

- Aloia,MS, DiDio,P, Ilniczky, N. Perlis,ML, Greenblatt, DW, & Giles, DE (2001). Improving compliance with nasal CPAP and vigilance in older adults with OSAHS. Sleep and Breathing, 5, 13–21.

- Aloia MS; Arnedt JT; Strand M; Millman RP; Borrelli B. Motivational Enhancement to Improve Adherence to Positive Airway Pressure in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sleep 2013; 36(11):1655-1662.

- Powers MP. Wearable Activity Trackers Encourage Patients to Exercise. University of Michigan. https://labblog.uofmhealth.org/rounds/activity-trackers-tools-for-patient-behavior-change. Published May 11, 2016. Accessed July 10, 2020.